Bugwood image credit |

Hi! My name is Spud and I’m a friend of Chip Tynan’s. We met in the produce section of a local grocery store a couple of years ago and found we have a mutual interest in abnormal plant growth. In the months ahead we’ll be featuring many examples of plant oddities, including fasciation and other unusual and aberrant plant growth forms as well.

|

|

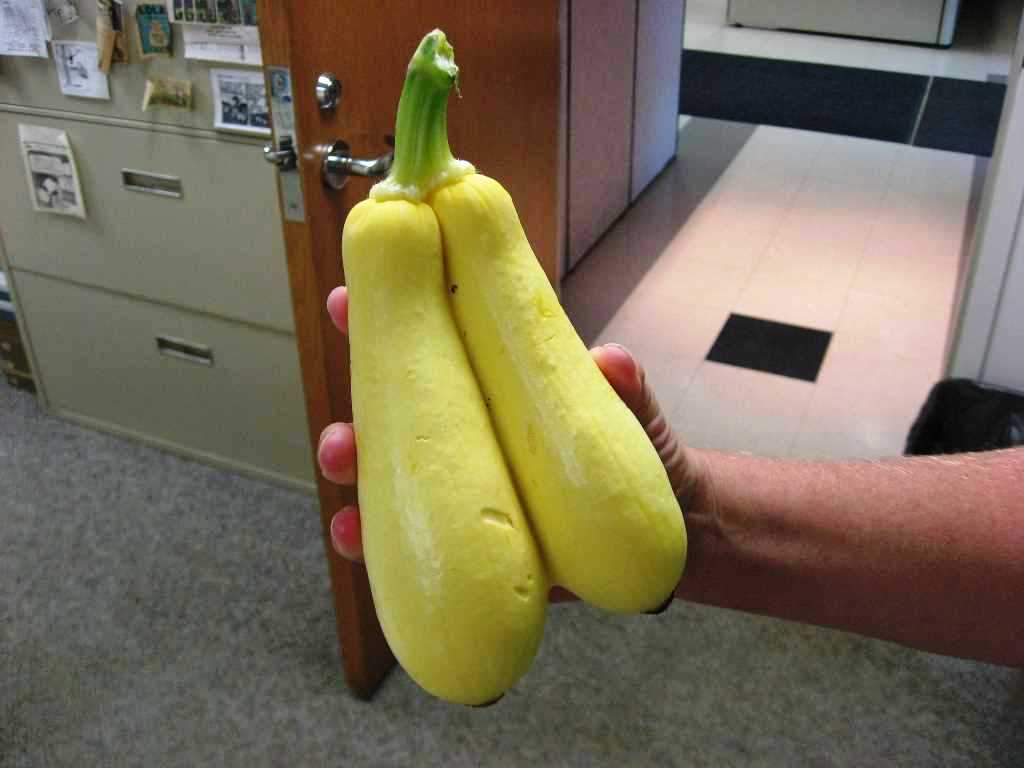

Squash twins

These conjoined squash resulted when a single ovary split in two when the flower formed. |

|

Fasciation

Perhaps you’ve chanced upon an oddly flattened branch on a plant growing in the wild or your own home garden? Or maybe you’ve seen a floral arrangement containing a curiously flattened stem? Fasciation is the term used to describe such aberrant growth, a word derived from the Latin fascia - to fuse. Fasciation occurs in both herbaceous as well as woody plants, forming in the latter case on rapidly growing softwood before the tissue has hardened. The causes of the condition are not entirely understood. Spontaneous mutation accounts for some, but virtually any factor, including environmental conditions, insects, diseases, or physical injury, that damages the meristematic tissue at the growing tips can result in fasciation. More often than not, the cause is non-infectious.

While any growing part of a plant can become fasciated, perhaps the most spectacular and frequently observed forms occur on stems and branches, resulting in broad, flat, ribbon-like growth often terminating in baroque twists and curves. Lily growers frequently find fasciated stems, especially in Oriental lilies where the condition typically results in an unusually large number of flowers. The flowers of the old fashioned Cockscomb celosia (Celosia argentea var. cristata) are fasciated, an inherited trait that comes through from seed. .

|

|

The 'King's Crozer'

My pal Chip has a walking stick he calls the 'King's Crozer". It was collected from a tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima) that sprouted literally from a crack in broken paving in a non-public maintenance area on the Garden grounds. It was cut to the ground many times, but survived for several years. Throughout its short life it produced multiple, fast-growing, broadly fascinated stems in addition to the King’s Crozier. |

|

It’s gone Spiral!

Over the years my pal Chip has obtained many specimens of fascinated stems from purple smokebush (Cotinus coggygria ‘Velvet Cloak’) from shrubs growing on the Garden grounds. Why that it, is open to speculation. Most of the specimens are severely pruned every winter to force the production of new growth which produces the

most vibrant leaf coloration. In addition, occasional outbreaks of gregarious caterpillars have been observed feeding on the new growth on branch tips during summer. Either of these factors may damage meristematic tissue, resulting not only in fasciation, but more rarely, the occasional spiral fasciation.

|

|

When a bad plant does good

Dames’ rocket (Hesperis matronalis) is an old-fashioned garden flower that has fallen out of favor in recent times due to its invasive nature. The Midwest Invasive Plant Network lists it as an exotic invasive species for Missouri and the Midwest and recommends that it not be planted. My pal Chip was delighted when he chanced upon this highly fascinated specimen with a broad, ribbon-like stem. After photographing it, he did his part for the environment, and collected and dried the plant before it could scatter its crop of seeds.

|

|

An Outbreak of Fasciation!

My pal Chip has encountered fasciations in several species of Liatris. In this case, a number of Liatris aspera specimens growing in close proximity to one another in the Heckman Rock Garden during 2007, generated multiple fasciated stems, several of which terminated in tightly contorted spirals. This created a concentrated mass of nectar-rich flowers, a bonus for Monarch butterflies migrating through St. Louis City on their journey south to their wintering grounds in Mexico.

|

|

Double the Fun

Conjoined fruits are always fun to find in the garden, and there was an eggplant growing in the Kemper Vegetable Garden during 2013 that produced not just one, but several pairs of twins throughout that summer.

|

|

Double Redux

Harvest time is a great time for scouting for vegetable anomalies. Here’s a conjoined, unidentified dry Cucurbita pepo that my pal Chip found at a farm stand

several years ago

|

|

Here’s a conjoined Cucubita pepo, perhaps ‘Sweet Dumpling’ (or similar) squash found recently by our pal Tammy at a local farmers market. The presence of three distinct flower scars on the base suggest it’s not just a doubly, but a triply conjoined squash! |

|

Windows in Trees

On a recent trip to Oregon, my friend Chip visited a garden in Portland that has a small grove of Pacific madrone trees (Arbutus menziesii). Several specimens had branches with curious growth, apparently formed by the grafting of adjacent stems, most likely when the twigs were young and pliant. He was left to ponder whether this occurred naturally, or by the creative endeavors of an artistic pruner with a sense of humor?

This “window” is reminiscent of a jug handle.

|

|

The Hungry Tree

There is a historic residence in downtown St. Louis that mounted a steel I-beam in front of an aging brick wall to protect the structure from the fenders of cars in their parking lot. An opportunistic seed from a tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) sprouted at the base of the wall many years ago and grew up in the space between the wall and the beam. Over the years, the tree grew around the beam in such a fashion that it appeared it was attempting to ingest it. It was only partially successful by the time it lost its head to the pruners saw.

|

|

Faces in Nature – 1

A cloud catches the rays of the setting sun in the aftermath of a late afternoon storm in south St. Louis. Do you see Pinocchio?...or the face of an angry troll with his wind-blown hair on fire?

|

|

Faces in Nature – 2

Seen at the beautiful Lan Su Chinese Garden in Portland, Oregon – the face in this rock seems to say “Excuse me, I have a hair plant in my eye”.

|

|

Addition by Subtraction

My pal Chip tells me that one of the most frequent questions he’s asked is “is it time to prune my hydrangea back?”. This amazing 2-story specimen of PG hydrangea (Hydrangea paniculata ‘Grandiflora’) stands as a testament to the concept that less is more. Remove the pruner from the equation for a decade or two, and even a relatively homely cut-back shrub can achieve star stature in the absence of annual human intervention.

|

|

Mysterious Curiosity: Animal, Vegetable, or….Slime Mold?

The exact identity of these fascinating growths found on the leaves of a tropical foliage plant in a container display at a retail nursery is yet to be determined, but it is suspected that they are fruiting bodies of a slime mold growing upon, but not injuring the plant.

|

|

Reversions

Reversion is the word used to describe new growth on a cultivar grown for a unique characteristic that “reverts back” to a form more typically found on the parent species. In this case, this purple leaved cultivar of our native Ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius ‘Diablo’) has produced a branch with green, rather than purple leaves. In order to preserve the visual integrity of the purple-leaved ‘Diablo’, this green stem should be pruned off and removed, lest the entire shrub were to revert to all green stems over time.

|

|

In this example, this variegated tapioca (Manihot esculenta ‘Variegata’) has also produced a reversion with all green leaves. As is often the case, this shoot is more vigorous and with larger leaves than the variegated portions. It will eventually overwhelm and out-compete the variegated parts of the plant. Shoots such as these should be pruned out completely, or cut back into wood containing variegated growth below the point from which the green shoot has arisen. |

|

Teratology

These curious growths on the leaves of an otherwise healthy ‘Red Russian’ kale seedling are reminiscent of an illustration of a cabbage leaf with “hornlike excrescences” that appeared in the book “Vegetable Teratology”, by Maxwell T. Masters, which was published in England by the Ray Society in 1869.

Teratology is a term used by Victorian botanists to describe the study of plant “monstrosities” and other abnormal or aberrant growth forms.

|

|

More Fasciations

My pal Chip recently fielded an email from a lady in Montana who took a picture of a tree in Arizona exhibiting unusual growths. Needless to say, he was enthused to realize it was a unique fasciation, but the identity of the tree was unknown. Fortunately, pictures of the flowers, leaves and fruit were also included in the message. Enlisting the expertise of a colleague in Research, the tree was determined to be the Mescal bean (Sophora secundiflora), a native of Texas, New Mexico, and northern Mexico that can be cultivated in gardens through the arid regions of the southwest.

It’s also known by the common names of Texas mountain laurel, and frijolillo. Identification was confirmed by comparing the flower and foliage images to preserved specimens in the Gardens herbarium. Interestingly, the process also turned up a collection of another fasciated branch already present in our herbarium.

Through the kind generosity of the photographer, who is allowing the Garden to utilize her images, they are now available to researchers worldwide, and can be viewed online in our Tropicos database at this address http://www.tropicos.org/Name/13033015?tab=images

|

|

Repurposing Aggressive Exotic Plants

Some of you may be familiar with the recent environmentally friendly trend for converting invasive bush honeysuckle shrubs into one-of-a-kind furniture pieces (see http://www.woodworms.net/ ).

Many gardeners utilize tall bamboo stems as handy garden stakes. When the undertaking of the Herring House restoration of the (former) Cleveland Avenue Gatehouse began in earnest this spring, it necessitated the removal of the aggressively spreading yellow groove bamboo (Phyllostachys aureosulcata) that had completely overwhelmed the landscape surrounding this Victorian structure. Kemper staff horticulturists were quick to recycle many of the culms into several handsome, sturdy structures that have supported vegetable vines as well as tomatoes this summer.

|

|

My pal Chip has a cherished gift given to him a number of years ago by a creative Master Gardener who harvested a very robust trunk from a castor bean plant (Ricinus ‘Zanzibarensis’) . After pruning off all the leaves and drying the stem thoroughly, she sanded it to a smooth finish. Having a hollow stem between each solid leaf node, it produced a lightweight, but surprisingly sturdy and very serviceable walking stick. |

|

Year of the fasciated Sweet Potato

My pal Chip tells me he had never seen a fasciated sweet potato vine before this year. Within a matter of weeks in late summer 2016, three fasciated vines have been brought to his attention. Two appeared in home vegetable gardens on edible sweet potatoes – one in Madison County, Illinois, the other in Franklin County, Missouri.

|

|

The third specimen is a purple leaved ornamental vine from an annual flower bed in St. Louis County having remarkably twisted and contorted growth terminating in a broad, flat, double-tipped point. |

|

When is a Palm not a Palm?

The answer is when it’s a Madagascar palm (Pachypodium lamerei), which is actually a member of the Dogbane Family (Apocynaceae) and native to the Island of Madagascar. Though heavily armed with thorns, the Madagascar palm is not a true cactus, but actually a succulent.

This amazing specimen, photographed in a conservatory at the University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley, CA caught the eye of my pal Chip because of its astonishing “crest” of fasciated growth.

|

|

Leaning tree doing push ups.

There is a tree along a pathway at Point Reyes National Seashore in California that blew down decades ago, burying several sturdy branches in the process. These serve as “arms” holding the trunk up and forming an archway over the path.

Over the years, side branches along the length of the trunk have oriented their new growth upright in the direction of the sun, creating their own mini grove of elevated forest.

|

|

Pig tails on fruits

This deformation on a Gala apple was caused by aberrant growth of the flesh tissue (hypanthium) that pushed the pedicel (stalk) off center.

|

|

This curious excrescence that erupted through the skin of a green tomato was quite fragile and inadvertently broken off shortly after this picture was taken. |

|

Reach Out and Touch Someone Today

I think this tree got tired of waiting and decided to hug itself.

|

|

How about a hand shake

Here’s how shrubs shake hands when greeting one another. |

|

Hugs aren't just for people or plants

Group hugs are always THE BEST. |

|

Burls on Trees

Burls form as a consequence of abnormal proliferation of xylem tissue cells in the vascular cambium. The net result are woody masses of crazy grain. If you visualize “normal” wood grain as parallel strands of string, then the grain of burl wood is like a twisted, messy ball of twine covered by bark. The massive burl in this image developed high up on the trunk of a coast redwood tree in California

|

|

No two burls are alike. Stare at the picture of this burl for long enough and your imagination may reveal the shapes of many fantastic, whimsical figures residing within its confines. |

|

Burls such as these growing on a bigleaf maple in the northwest, often serve as platforms upon which unique habitats develop. In this environment they are frequently colonized by mosses and ferns, followed by seedlings of trees, shrubs and other flora, as well as the fauna that typically associate with these species. |

|

Galls are everywhere

One of the more curious galls found on trees is the wool sower gall (Callirhytis seminator). It’s a stem gall found only on white, chestnut, and basket oaks, but is not found on any red or black oak species. It’s a spring gall, but does not occur every year.

Wool sower galls can be surprisingly large, upwards of two inches or more in diameter, but lightweight. When fresh, it is typically pure white with pink spots, but eventually darkens with age. It appears to be woven from woolen threads and has a soft, spongy texture. It does not damage the twigs or stems of its host.

|

|

Many tiny larvae develop in seed-like structures within the cavity of the gall, as seen in the image of a different specimen dissected in the Kemper Center for Home Gardening several years ago /Portals/0/Gardening/Gardening%20Help/images/Pests/Galls_on_Trees379.jpg |

|

Fasciations are all around us

Dr. James Trager is a Restoration Biologist, and Staff Naturalist at Shaw Nature Reserve. Not surprisingly, he has a great eye for unusual forms of plant growth, and has kindly shared pictures of a number of fasciated specimens he has encountered over the years. This is a faciated flower stem on a wild hyacinth (Camassia scilloides) growing in the Whitmire Wildflower Garden. Contrast the size and number of flower buds relative to the normal infloresence of the specimen blooming to its left. |

|

This specimen is a fasciated Sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata). This is an introduced Asian species which was originally planted for forage, erosion control, soil improvement, and wildlife food. Unfortunately, it has escaped and invaded native plant communities, where it is considered an exotic, invasive weed, and is quite difficult to control. Team Spud supports the collection and destruction of any and all Sericea lespedeza plants, whether fasciated or not. |

|

Sumac Leaf Gall

Glenn Kopp recently found this curious leaf gall, which is new to the Spud Crew. Found in the Schnuck’s Childrens Garden, it’s an insect gall caused by the sumac leaf gall aphid, Melaphis rhois, which has a very complex life cycle.

|

|

The gall forms from a single egg laid on the underside of the leaf by a winged female. |

|

From this single egg, a series of all-female generations develop inside the gall. In late summer, a generation of winged females emerges from the gall and flies off in search of moss beds in which to colonize with both male and female offspring. This generation mates and produces the eggs that will be placed back on sumac leaves the following spring. |

|

Aliens on my rose bush!

A recent correspondent from the state of Maine walked into her garden one morning and was surprised to find strange, spiny growths on her rose bush. These are rose pincushion galls, also known as mossy rose galls. They are caused by yet another tiny Cynipid gall wasp (Diplolepis rosae), that lays her eggs in leaf buds in the spring. The wasps have one generation per year.

This same wasp species also occurs in Europe where these galls are known by the common names of bedeguar and Robin’s pincushion gall. As the galls grow and develop, they change color from green to red and eventually to reddish-brown, as the larvae mature within. Mature larvae overwinter in the galls before emerging as adults the following spring to start the next generation.

Pictures of a similar spiny gall, the blackberry pincushion gall, can be viewed on our Plant Finder page at this address https://tinyurl.com/ybfauw58

Despite the similarity, the blackberry gall is caused by a different species of gall wasp.

|

|

Text |